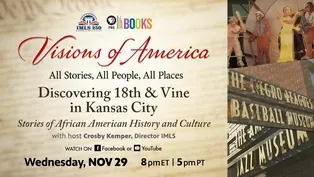

Visions of America

Discovering 18th & Vine in Kansas City

Episode 3 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Crosby Kemper explores the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and the American Jazz Museum.

Join Crosby Kemper as he explores two famous landmarks located in Kansas City's "18th & Vine District", the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum (NLBM) and the American Jazz Museum. Kemper leads a conversation discussing the importance of the NLBM for African-American culture in Kansas City, and he delves into the critical role of African Americans and their culture in jazz at the American Jazz Museum.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Visions of America is a local public television program presented by Detroit PBS

Visions of America

Discovering 18th & Vine in Kansas City

Episode 3 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Join Crosby Kemper as he explores two famous landmarks located in Kansas City's "18th & Vine District", the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum (NLBM) and the American Jazz Museum. Kemper leads a conversation discussing the importance of the NLBM for African-American culture in Kansas City, and he delves into the critical role of African Americans and their culture in jazz at the American Jazz Museum.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Visions of America

Visions of America is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship- Hello, everyone.

I'm Crosby Kemper, director of the Institute of Museum and Library Services, and welcome to "Visions of America: All Stories, All People, All Places."

In this episode, we're in Kansas City, Missouri's historic 18th and Vine neighborhood to visit not one but two museums that chronicle this community's contributions to a pair of uniquely American pastimes, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and the American Jazz Museum.

"Visions of America" is coming up next.

(gentle music) While we've already seen a few truly historic structures as part of our travels to some of the country's lesser known but no less important museums, sometimes it is not as much the space, but the history that is being preserved inside that is the most important.

We're here at 18th and Vine near downtown Kansas City, now the joint site of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and the American Jazz Museum, but we are also close to the heart of what was, in the 1920s and 1930s, a cultural explosion of music, baseball, and barbecue that challenged and changed America.

Jazz may have originated in New Orleans, but Kansas City developed its own big band style based on riffs, jams, and rooted in the blues, which filled countless nightclubs and dance halls with passionate patrons on a nightly basis.

Black-owned businesses were also flourishing in this neighborhood, like the nation's first Black-owned automobile dealership, and The Kansas City Call, a Black-owned newspaper, but perhaps the most successful business that originated here had to do with America's game.

This was the home to the Kansas City Monarchs, and, today, 18th and Vine is home to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, dedicated to telling the stories of those brave Americans who wouldn't take no for an answer.

The first person I'm meeting on our visit here is Bob Kendrick, the president of the museum, to get a tour of the exhibits here and talk about this important chapter in the story of America's pastime and how it still continues to resonate in the community today.

(gentle music) Bob, it's so great to see you and see you here in the Negro Leagues Museum, and it's an important moment in the history of The Negro Leagues Museum, because you're about to do a major expansion.

- Yes.

- But I wanna ask you this question.

Why is the Negro Leagues here in Kansas City at 18th and Vine?

- And that's a question that is commonly asked by so many of the folks who come to visit us is why is the Negro Leagues museum in Kansas City?

And the answer is actually quite simple, because Kansas City is the birthplace of the Negro leagues.

The leagues were formed right here in Kansas City, in this very area that we're in.

- [Crosby] A couple of blocks away.

- A couple of blocks away, the old Paseo YMCA, the building still stands.

We've now designated it as the home of the future Buck O'Neil Education and Research Center.

So we're saving that historic landmark, and then going to basically go full circle right back to the very building that it all started .

- Where it started in 1920.

- 1920.

- And so we're at the 103rd anniversary of the Negro Leagues.

It's a huge importance in American history because it highlights the segregation that was a part of our world for so long, too long.

There was Black baseball before the Negro Leagues.

- [Bob] Absolutely.

- And then there was something called the gentlemen's agreement.

Can you explain the gentlemen's agreement?

- The gentlemen- - It might not be called gentlemen today.

- Yeah, the gentlemen's agreement wasn't very gentlemanly.

- [Crosby] Right.

- But it basically was a verbalized doctrine that banned Blacks from playing on white Major League teams.

Again, I find it fascinating that there was nothing written.

- [Crosby] Right.

- [Bob] Just a verbalized agreement amongst players, managers, and owners that essentially said, if you allow a Black to play with you, you can't play with us, and that governed Major League Baseball essentially for the next six decades until Jackie Robinson really breaks the color barrier in Major League Baseball.

- Right, let's go take a look at the whole of this museum, this great museum, the whole story.

- Well, I can't wait to welcome you back.

Let's go do it.

- Okay.

Great.

(upbeat music) Bob you have brought us to a special place here.

- Yes.

- I'm leaning on the outfield wall of the Negro Leagues field, and tell me about the field.

What's the story of this?

- [Bob] There was some thought that went into how we laid out the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

So the field that you're talking about is called the Field of Legends, and it is a mock baseball diamond that houses 10 of 12 life-sized bronze sculptures of Negro League greats.

The significance being they represent 10 of the first group of Negro Leaguers to be inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

So that's how our All-Star team was chosen.

On the outside looking in is our friend, the late, great John Jordan Buck O'Neil, our most recent inductee into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

- [Crosby] The great ambassador of the Negro Leagues and Black baseball.

- Oh, absolutely, and in this capacity, he is managing this great All-Star team that we assembled, so what we hoped would happened was that our guests would walk in through the turnstiles, peer through that chicken wire backstop, see this incredible display, and we hope it gives them that desire that, "Oh, I can't wait to get out on the field, walk amongst the statues, take my pictures with the statues," but, you see, here at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, we segregate you from the field.

We wanted our visitors, particularly my younger audience, to at least remotely experience what segregation was like.

So, in the case of these tremendously talented and courageous athletes, they knew full well that they were good enough to play in the Major Leagues, so close to it, yet so far from it.

So, for most vantage points in the museum, you can see the field, but you can't get to it, and the only way that you're allowed to take the field here at the Negro Leagues Museum, you have to earn that right, and you do so by- - [Crosby] Know the whole story.

- Uh-huh, by learning their story, and as I say, by the time you've beared witness to everything that they had to endure just to play baseball, the very last thing that happens is now you can take the field.

- Now you can take the field.

(upbeat music) - So, Bob, we have now earned the right- - Yes.

- To be on the field with these incredibly great players.

These guys have become legendary, I think more legendary in their way that most of the great white ballplayers, with a couple of exceptions like Babe Ruth.

- Ruth, yes.

- Who certainly has become legendary, and they are larger than life, and I think that's one of the glories of this museum, is a bunch of larger than life folks.

- [Bob] And they did.

They inspired legions of kids to dream about the possibility of playing baseball.

- But it seems to me that's the importance of this museum.

- Mhm.

- Is those lessons, the lessons from these great figures.

- [Bob] Yes, and that's what we talk about.

We talk about not only the historical aspect that is so well-documented and substantiated here.

It's a wonderful slice of baseball and Americana, but the inspirational aspect of what this story represents may be as meaningful, if not more meaningful than the historical piece that this represents, and the life lessons that stem from this story of triumph over adversity.

You won't let me play with you in the Major Leagues?

I'll create my own league, and as I remind folks, when you stop to think about that, that is the American way, and so while America tried to prevent them from sharing in the joys of her so-called national pastime, it was the American spirit that allowed them to persevere and prevail.

What's not to love about this story?

It was just a matter of giving people an opportunity to have access to it.

(upbeat music) - If you're gonna talk baseball, you wanna talk to author and sports journalist Joe Posnanski, a former senior columnist for Sports Illustrated and columnist for The Kansas City Star.

Joe sat down with me during my visit here to help put the contributions of the Kansas City Monarchs, Jackie Robinson, and the Negro National League in perspective.

Tell us a little bit about that invisibility of the Negro Leagues and how this museum is making it visible.

- Yeah, I mean, for me, of course, it starts like every part of sort of my baseball writing journey.

It starts with Buck O'Neil, and I think what's so interesting is, for many, many, many years, 30, 40 years, Buck O'Neil would tell the stories that would later become famous, but he was telling those stories for so many years and nobody listened, and I got to know Buck sort of right when his fame was beginning to grow.

- Right.

- But the thing that always struck me was Buck used to say, "I told these same stories.

The stories haven't changed and nobody listened."

Nobody listened for so long, and I think there was a conscious effort to sort of ignore the Negro Leagues.

It's an ugly part of America, right?

Is the racism that prevented these great players from playing, and I think a lot of people didn't wanna look back.

A lot of African Americans didn't wanna look back.

There was a real pain in looking back, and Buck is the one that said, "No.

Yes, of course, there was prejudice, and, of course, there was hatred, and, of course, it was wrong, but there was so much joy and there was so many great players."

- [Crosby] Of course, famously, Jackie Robinson.

- [Joe] That's right.

- [Crosby] Was here for a year.

- [Joe] One year.

Exactly.

- Really, a lot less than a year.

A few months, not very happily.

- Right.

- It should be said.

On the other hand, it was his ticket in.

- Exactly.

- And it was the first step- - Willie Mays played just a few games in the Negro Leagues, you know, so there there are people on that end, and then there are people on the other end who, like Satchel Paige, who had an entire career, and then was able to be in the Major Leagues for a little while.

- But, on the other hand, Satchel really did, he created Satchel's All-Stars, and, actually, the Negro Leagues was substantially about that.

The seasons were sometimes only 60 or 80 games long.

- [Joe] Yeah.

The league was just run differently.

I mean, a lot of them, you know, there were league games that were usually played on Sundays, double-headers after church.

- After church.

They'd reschedule church.

- Very famously, yes, they scheduled church a little early for the games, and between the league games, they played every day, and so sometimes they played each other, sometimes they played factory teams and farm teams, but the league was set up very differently, which, you know, makes it very difficult to look at, say, stats.

You can look at the stats that have sort of become official and they are league play.

They're the highest level of play, but they don't give you the full flavor of what a full season was like.

- And they don't give you a flavor, which there was a substantial amount of, which is more and more the statistics around this are being dug up, is in the barnstorming, they would frequently play All-Star teams from the Major Leagues or actual Major League teams, the Yankees frequently, and the records, as it turn out, of those games are pretty favorable to the Negro League players.

- Yeah.

The Negro League players won most of those games.

I mean, they had a, and this was against very, very high-level competition.

I mean, Bob Feller would have a team.

Joe DiMaggio would play in these games.

Ted Williams would play in these games, so we're talking the highest level, and Buck used to talk about that.

Buck O'Neil used to always say, "Well, it's no surprise that we won those games, because those games mattered more to us."

The greatest players had incredible respect, almost to a man, for the players in the Negro Leagues, and Buck used to talk about that too.

He said, you know, "Mot only does sort of game recognize game, you know?

That idea, but, also ,they didn't feel threatened."

- Right.

- You know?

So Joe DiMaggio would say, point blank, the greatest pitcher he ever faced was Satchel Paige.

(upbeat music) - Of course, as we mentioned at the beginning of the program, baseball is just one side of this story when it comes to preserving the cultural legacy of 18th and Vine.

Just a few steps next door, and you're dropped inside an immersive world dedicated to a truly unique American art form, jazz.

It's in the American Jazz Museum that I spoke with a few more experts about this community's rich musical heritage.

Muriel, I wonder if you would tell us a little bit about why the American Jazz Museum is here at 18th and Vine in Kansas City.

- Well, we are fortunate to be part of the community.

We are in the area that jazz grew up, and we are so interested in not only the history of our musicians.

We say this is not a Hall of Fame.

This is a collection of ideas and dreams that flowered into what became Kansas City jazz.

So, because we are part of the community, we are representing the music, the neighborhood, the people who attended these concerts, the people who gave lessons, the people who made the life of these musicians better by being their neighbors and being their friends.

- And, Chuck, the neighborhood was pretty incredible.

18th and Vine was the center of jazz and a whole lot else.

One of the reasons that jazz happened here is that Kansas City was known as the most wide-open city in America.

Why was it known as that?

And what was this neighborhood's contribution to it?

- Well, 18th and Vine was, during the days of public segregation, was the heart and soul of the African American community.

Buck O'Neil, a great ballplayer, told me that when someone would come to town from, like, Lexington, Missouri, and they wanted to find a relative, they would ask where that relative was.

Maybe they didn't know where he lived, where that person lived, so they would, say, stand on the corner of 18th and Vine and they'll walk by there at some time, and there were clubs here, but, also, it was the business district.

The Lincoln building, which was established in 1921, formed the cornerstone of the district, and it was the home of offices for professionals, lawyers, dentists, and anything that was denied anything or service that was denied downtown, African Americans could get here.

- And the influence of this is important in many larger senses, not just the history of jazz, but the history of literature as well, Arnold.

Langston Hughes grows up not far away from Kansas City.

His mother's here, so he ends up coming to Kansas City and experiencing this culture.

Clearly, it's important to him as he gets to Harlem and the Harlem Renaissance, which really, in some ways, starts here with Langston, with Aaron Douglas.

Lincoln High School creates part of the African American culture, graduating people like Aaron Douglas.

What would you say about Hughes and Ellison and their relationship to jazz?

- Well, I think it's crucial to their development, and their work as writers, absolutely crucial.

I think one thing that strikes me is that, even as a professor of literature and as a literary critic and so on, we have to see music as being the central art form of Black America.

Hughes saw it that way.

I think, to some extent, Ellison saw it that way also, even though he was very interested in all kinds of literature, but Hughes saw it and understood it, and the great task of the writer was to somehow capture this spirit of virtuosity of jazz musicians in their work.

- Between '20 and '40, this was the conservatory for jazz.

This was where the seeds were planted, where the people learned their lessons, where, you know, it just grew.

Of course, then they have to go off and practice their art form, and they went around the world.

- One of the things that really also set Kansas City apart is there was a really strong music education program in the in the grade schools and also the high schools, and it was started by Major N. Clark Smith, who was the bandmaster at Lincoln, and Charlie Parker was really the beneficiary of that too.

I mean, he played in the marching band at Lincoln, and he played also in the the orchestra at Lincoln too, and then, after school, there was a long tradition of the tradition being passed on from older musicians to younger musicians.

We saw that with Ahmed al-Din.

He continued that tradition.

Charlie Parker learned from Buster Smith, and so they passed the tradition on to the next generation, and that's still happening here in the Blue Room.

If you come here on a Monday night for the Blue Monday session, you'll see a lot of young cats with their horns waiting to get up on stage.

- Yes.

Through the American Jazz Museum, we have Jazz Academy, which starts with junior high school students through high school students.

We had a young man who was our intern here, and he said, "Ms. Muriel, I can't come in on Friday."

I said, "Oh, is everything okay?"

He said, "Well, I got a gig tonight.

I'm like, "Okay, all right."

And he was just a junior in high school.

- In the spirit of the dual nature of this building and the two museums and houses, it turns out Arnold Rampersad knows a little something about baseball in addition to his deep knowledge of literature and jazz.

I couldn't pass up the opportunity to ask him about his take on one of the greatest ever to play the game.

Arnold, one of the less well-known parts of Jackie Robinson's biography, his history, is that his first professional baseball experience was here in Kansas City with the Monarchs.

It wasn't planned, but it happened and was his first professional experience.

- Yes, and, I mean, it's very important because, at UCLA, where he was on the baseball team, he didn't do very well.

Who knew that he would become, you know, what he became eventually?

But it did start with Kansas City, and it started with a sort of accident of his being at a park and a ball rolling at his feet.

I mean, this story is almost too good to be true, and he throws the ball to the player and the conversation ensues and he ends up in Kansas City.

- I think there's also one other story in the Jackie Robinson story that is important, and that could have ended up ending his having any kind of chance of career, but when he was in the army during World War II, he was court martialed.

- Yes.

- Because he stood up to a bus driver, and he felt the bus driver was not treating him right as an officer, which he was.

- Right.

I'm sure the bus driver was not treating him as an officer, and it could have all ended right there, but he stood his ground, and the remarkable thing is that he survived that, which could have ended almost his life, his mature life, and then Branch Rickey went on to choose him.

I think he chose him in part, I would suppose, because of how he comported himself in that situation.

- But he wouldn't have necessarily been picked for baseball because of his batting average.

He was really picked because of his character.

- His character.

Yes.

(upbeat music) - While the 18th and Vine community initially flourished in the 1920s, '30s, and '40s, economic hardships hit the neighborhood hard in the back half of the 20th century, but thanks to a renewed investment in this neighborhood and the tireless efforts of those like Reverend and Representative Emanuel Cleaver, 18th and Vine is once again playing the role of vital cultural center.

Since no visit to Kansas City is complete without a little local barbecue, I met Congressman Cleaver at Gates Bar-B-Q, which has its own roots in this neighborhood as well, to get both the congressman and our friend Ollie Gates' take on the incredible cultural gifts that the African American community has given to our country.

And so, Ollie, 1946, your father inherits, buys Henry Perry's old barbecue, the Ol' Kentuck.

We've got a picture of it right back here, but the Ol' Kentuck, when you go back to the '20s and the '30s, it was the barbecue place for 18th and Vine, for the jazz musicians.

- Yes.

- And they used to come and play.

- It was a combination.

- Right.

- Yeah.

- It was a club.

- A speak-easy.

(Ollie chuckles) - And, I mean, you're still, today, you can get good liquor here at the Gates Bar-B-Q.

I used to like going- - But it's legal today.

- It's legal.

(Ollie chuckles) That reminds us.

Yes, that was prohibition in those days, and though you've expanded way beyond 18th and Vine in many ways, 18th and Vine is still the home.

- Oh, absolutely.

- And the two of you together have been the two people who have tried to restore, to rebuild 18th and Vine, the Negro Leagues Museum and the American Jazz Museum.

What can we do to tell the world about 18th and Vine, which was so important to the music of this country and we fed baseball players in the Negro Leagues out of Ol' Kentuck and elsewhere?

How can we tell the world about its importance?

- The world probably does not understand where some things came from, and what we need to do is make sure they connect it with Kansas City.

For example, the Negro Leagues were formed right off of 18th and Vine at the Paseo YMCA - The YMCA.

- [Emanuel] The home of Charlie Parker, Kansas City, right here.

Count Basie made this his home.

- [Ollie] Satchel Paige!

- [Emanuel] Satchel Paige made this his home, and Buck O'Neil, and it could go on and on and on with great jazz players, you know, and I think, when you connect all of that, it was done in the middle of an African American economic center, around 18th and Vine, where, you know, if you think about it, there were Black business back in the 1940s and '50s that were successful.

- [Crosby] A huge amount of Black businesses.

Hotels, barbers, tailors, you name it.

All kinds of retail.

The first Black automobile dealership owned by a Black man was in Kansas City.

- 18th and Vine.

You're absolutely right.

- [Crosby] It was a very important place for small businesses.

- [Ollie] It's the only thing in this country that's known nationally, 18th and Vine.

- [Crosby] Absolutely.

- [Ollie] Internationally.

- Black culture, in this city and in this country, has made such a huge impact, and it's in food, barbecue.

That's my favorite version of it, but there's lots and lots of other things as well.

Jazz, baseball, politics, the movies, TV, et cetera.

We're coming up to the 250th anniversary of the country.

How do we celebrate that?

How can we use that celebration to celebrate the things that we've just been talking about?

- This is an area rich with history, and we oughta exploit it.

I think people all over need to know some of the characters in Kansas City.

Seldom Seen was a character in Kansas City.

Jay McShann.

All these magnificent jazz artists lived here, and 18th and Vine jumped and jumped and jumped, and there are a lot of us who believe there's still some jump left.

- So, you know, jumping is, of course, a jazz term, but it's pretty much a term for any live culture, including cuisine, including food.

So is it still gonna jump, Ollie?

- I hope so.

I'm with you.

- Okay.

- I don't have much longer here, the time that I have.

- You look in pretty good shape, I gotta say.

- Yeah, for 91 years old, pretty good shape, but, you know, you didn't turn 91.

(group chuckles) - The story of 18th and Vine is a civil rights story, a story of courage and the enduring power of sports and music to fulfill American dreams, dreams of freedom and equality.

This is a community that has seen its fair share of ups and downs, and like any good come-back tale, it's clear after a visit here that this neighborhood story is still being written.

I'm grateful to all our guests for providing some heartfelt insights into the vibrant history of Kansas City's African American heritage, and I hope that you made a few of your own discoveries along the way as well.

After all, that's what museums and libraries are for.

I'm Crosby Kemper, and I'll see you next time for another episode of "Visions of America: All Stories, All People, All Places."

(upbeat music) (gentle piano jingle)

Preview - Discovering 18th & Vine in Kansas City

Crosby Kemper explores the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and the American Jazz Museum. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipVisions of America is a local public television program presented by Detroit PBS